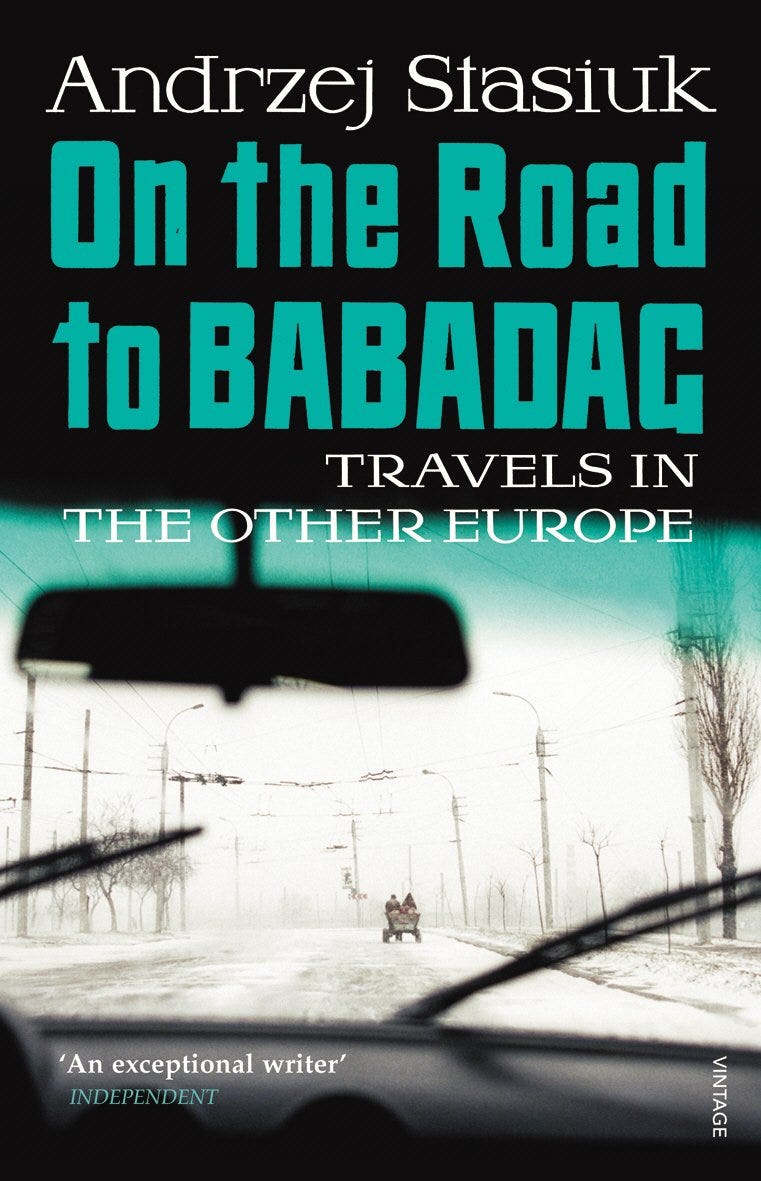

nothing new: Andrzej Stasiuk's monastic Road to Babadag

Travel is a meditative exercise in the Polish writer's 2004 exploration of a Europe forgotten.

Since the turn of the century, Eastern Europe has arguably changed more than any other part of the world. The fall of communism signaled a massive transfer of wealth that westernized everything. Today Prague is Boston, and even areas like Tallinn, places international tourists would never check out, are fast on your new Bumble match’s next “crazy adventure.”

This is not the Europe Polish writer Andrzej Stasiuk explores in Road to Babadag: Travels in the Other Europe. He’s never been to France or Spain. Mingling in the discotheques of Warsaw or Budapest with cool foreigners talking about their art is definitely not for him. Tourist-filled cities are just a “mirror of elsewhere.” But he is no nationalist. Stasiuk has compared Germany to a well-oiled machine and Russia to a feral animal. The mysterious, solemn land in between is what he writes about.

The west, the Europe well known, barely comes up in this travelogue. It’s like it doesn’t even exist. Instead, you are immersed in an ancient Europe that hasn’t changed for generations. Village outposts in the black mountains of Transylvania. Checkpoints at the border, Moldovan gypsies, laborers who “measured time in shots of liquor” while waiting for something to happen. Cafes in Ukraine with no menu that only sell cups of brandy. He stays in the homes of strangers in Slovakia, in half pitched tents over stone, and travels by bus, boat and taxis led by mysterious Romanian handlers who finesse connecting him to his destination just in time. This was during the first half of the aughts, before the Internet was ubiquitous (I remember having to pay by the minute). The whole time, Stasiuk carries an old map. These days no one really gets lost because GPS has optimized travel. But it’s also has made it too precise, leaving no room for a little improvised adventure. Stasiuk gets lost. And reading him just getting from place to place is like seeing someone pull off a magic trick.

Stasiuk himself barely exists on the page, despite narrating in the first person. You never know where he is going. The book is like one long ambient trance. He travels through flyover soviet satellite states like a ghost just to find the grave of Romanian philosopher Emil Cioran, or to simply witness a lady sweep the steps in a Slovakian town that doesn’t exist on a map. Here’s him one morning in a town in Northern Hungary:

I stood in that preternatural silence, smoked a cigarette, and thought that all mornings in the world should be like this: we wake in absolute peace, in a foreign city that has no people in it, and everything around us is a continuation of sleep.

Like Polish journalist Ryszard Kapuściński, Stasiuk has eyes for the decrepit, the forgotten and mundane. He is drawn to small details, places that haven’t been seen for decades. He described the rain “darkening a mountain range like water on fabric. Later, “A wet December covered Zemplén like a curtain.” And I love how he analogized traveling:

In a country you know nothing about, there is no reference point. You struggle to associate colors, smells, dim memories. You live a little like a child, or an animal.

Travel today is very different. In Romania, a random man approaches Stasiuk and asks if he needs a room. The man said he knew a Babushka (old lady) who provided housing. Stasiuk passed on the offer because he was in no hurry, but eventually located the woman himself, who asked in Russian if he had “god in him” (You ain’t gonna find Airbnb hosts like these). A passage about moving her chair is a microcosm of Stasiuk’s approach to travel.

When I moved the chair out to hold my backpack, I felt like a criminal, as if I were destroying this piece of dark-brown furniture by exposing it to the present moment, that it would die as a sea creature dies when wrenched from the depths to the surface.

Stasiuk doesn’t want to disrupt anything, not even move a chair. He wants to disappear into these small worlds, witnessing them exist as they always have.

I’ve seen this book compared to Kerouac, a sort of slavic On the Road. There’s a little bit of a rhythmic beat-like energy in the book, but Babadag is a little different. On the Road is flashier…and a lot more annoying. For all its movement, Babadag is very much about standing still, being present wherever you are. He goes places and almost meditates on them. On the Road is always moving, always performing. It’s kind of exhausting. The second half of Babadag falls off a bit because it reads more like a retrospective compared to the first half, which puts you squarely in places. But it’s a good read overall, especially these days when…you know. Big city travel is nonexistent. People have been turning to road trips, to explore places without a lot of crowds. In that way, Stasiuk’s travelogue Road to Babadag is a perfect map to nowhere.