What is DWP really about?

forget the bribes and fake lawsuits for a moment. think ticking security time bomb that no one is fixing.

To paraphrase Conor Oberst: the picture is way too big to look at because our eyes can’t open wide enough.

The LA Department of Water and Power saga is a lot like that. It’s such a vast ocean that it’s tough to really get a sense of the true problem. Stories come out in slow drips, stripped of any larger context or meaning. Taken in all at once, the saga makes you either horribly confused or horribly depressed.

But forget the bribes and fake lawsuits for a moment. Think large-scale grid hack that would leave the city in chaos. This story is about the chronic dysfunction of the largest public utility in the country, which is hoarding water that has been stolen in the first place, and the lengths to which our suited masters go to benefit from that dysfunction. DWP provides the most elemental services to 4 million people, and if that stops, LA is so fucked. There have been indications that the DWP is pretty vulnerable to a cyber hack. A report last year in Bloomberg, citing the cyber security firm Dragos, said American utility systems are very susceptible to cyberattacks. And it used LA as an example.

Back in 2015 the city of Los Angeles redacted a report by the consulting firm Navigant, which in part blasted DWP’s security infrastructure:

Past assessments by LADWP security staff and the recent assessment conducted by Navigant have revealed a number of factors that limit the Department’s ability to mitigate security threats and vulnerabilities, including a lack of formal cyber and physical security processes, limited risk assessments, constrained resources, and limited executive level support.

The report also rested blame on management:

Moreover, there is little oversight from senior management and executive leadership due to the lack of formal processes and accountability . . . . the Department is not able to appropriately prioritize cybersecurity issues on an enterprise level. Furthermore, LADWP is not able to track the completion of critical cybersecurity projects.

This contradicted what DWP told the federal government in 2013 regarding its infrastructure. A DWP official said the utility followed guidelines for its critical infrastructure control systems, firewalls and encryption methods (emphasis mine).

LADWP maintains an in-house inventory system, and utilizes industry available software to inventory computer systems on the network and to ensure that security patch levels and antivirus signatures are up-to-date. LADWP has software and license management procedures to assist users with software compliance. These practices meet the requirements of the NIST “Asset identification and management” practice.

Following the damaging Navigant report, the city apparently hired a former CIA security officer named Robert Bigman to get a sense of what kind of shape DWP’s IT system was really in. It wasn’t looking good. Bigman, who reportedly briefed Garcetti, Feuer, and DWP officials, said a scan of the LADWP billing system identified over 4,000 unpatched vulnerabilities that could be exploited by cyber attackers. From a recent claim against the city by Ardent:

Bigman personally met with and informed the entire LADWP Board and then LADWP General Manager, David Wright, that the cyber hygiene of the LADWP System was, by far, in the worst condition of any IT system Mr. Bigman had ever assessed – bar none.

And if you’re to believe Paul Paradis, by the time him and his company, Aventador Utility Solutions, were hired by the city to fix DWP’s security issues, the problems were pretty urgent, like, Russians-hacking-the-grid urgent, and Aventador was equipped to fix them. It did its own analysis of the utility’s IT system, telling the city:

Connection to these systems demonstrates [sic] will enable an attacker to shut off water and power from across the Internet. Unauthorized access to the control and SCADA environment can directly impact public health and safety.

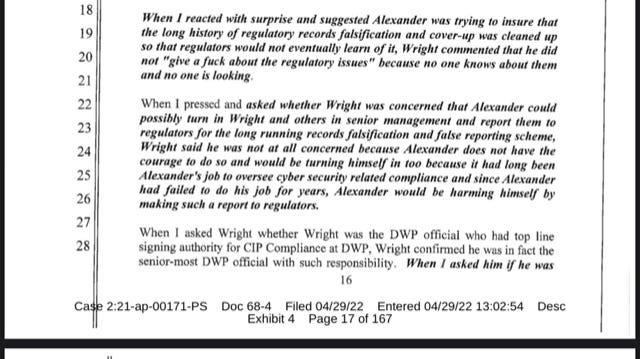

These problems were confirmed by former DWP executives, according to Paradis, who covertly recorded them at the direction of the FBI as part of the government’s criminal investigation into DWP. According to Paradis’ briefings to the FBI of one meeting with David Alexander, DWP’s former chief security officer, DWP has been falsifying regulatory records for the past 15 years “to cover up non-compliance with CIP standards and other regulatory requirements.”

One of the ways DWP did this was by self-reporting small violations so it could avoid regulators discovering bigger problems, according to Paradis. He went on to quote a meeting with former general manager David Wright, saying he did not “give a fuck about regulatory issues” because no one knows about them and no one is looking.

DWP officials also made sure other companies wouldn’t get cyber work with the utility so as to prevent them from uncovering regulatory violations, according to Paradis.

In the end, it was Paradis’ company that got millions in no-bid contracts to address security flaws. It apparently had former NSA officials working for it. But the company was named after a sports car in Grant Theft Auto and listed its office as an oceanfront condo in Santa Monica. People I’ve talked to say Aventador was not going to be the company that would fix DWP’s problems—and maybe DWP didn’t want it to. Maybe that’s why it got the job in the first place. And also because it was a thank you to Paradis for representing both sides of a billing lawsuit against DWP, taking millions in kickbacks as a result, and making Mike Feuer and Eric Garcetti look good.

DWP is one of the largest sources of revenue for the city. It has a budget of somewhere around $5 billion. Almost 20% of what we are charged on our utility bills goes straight into the city’s general fund so it can spend money on whatever it wants, whether it be creating a class of criminals so the LAPD can incarcerate or murder them, or enrich strangers from far away places like Paul Paradis. DWP is about a lot more than greed and saving political careers, but also about our safety. Who’s looking out for it?